The most important Roman source book about architecture is Vitruvius’ De Architectura known as the Ten Books on Architecture, in English. Vitruvius’ book was a very important source for architects during the Renaissance, such as Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, Donato Bramante and Andrea Palladio. Here is the section where Vitruvius describes the importance of proportion in temples and compares that to the proportions of the human body. (I have made one cut to the second section, to keep this sample lesson at a more manageable length.)

Here is the selection of Vitruvius’ text, in English, Latin and Spanish. Comparison of translations can be interesting and enlightening for anyone who knows these languages as a native speaker or as a student. (See also the translations into different languages on the Tacitus and Suetonius pages on this site.)

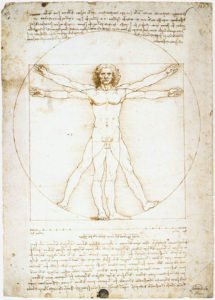

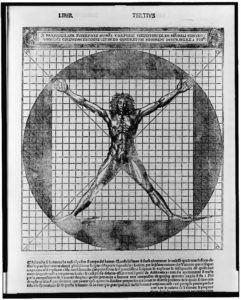

I have included three illustrations of Vitruvius’ famous description of human proportions, by Leonardo da Vinci (the most famous of these) and by two others, Fra Giocondo and Cesare Cesariano, who were contemporaries of Leonardo.

Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, Book III, Chapter I, sections 1-4.

[1] The design of a temple depends on symmetry, the principles of which must be most carefully observed by the architect. They are due to proportion, in Greek ἁναλογἱα.* Proportion is a correspondence among the measures of the members of an entire work, and of the whole to a certain part selected as standard. From this result the principles of symmetry. Without symmetry and proportion there can be no principles in the design of any temple; that is, if there is no precise relation between its members, as in the case of those of a well shaped man.

* Vitruvius here uses the Greek word ἁναλογἱα, transliterated it is “analogia” which in this context means ratio or proportion.

[2] For the human body is so designed by nature that the face, from the chin to the top of the forehead and the lowest roots of the hair, is a tenth part of the whole height; (…) The other members, too, have their own symmetrical proportions, and it was by employing them that the famous painters and sculptors of antiquity attained to great and endless renown.

[3] Similarly, in the members of a temple there ought to be the greatest harmony in the symmetrical relations of the different parts to the general magnitude of the whole. Then again, in the human body the central point is naturally the navel. For if a man be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centered at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too, a square figure may be found from it. For if we measure the distance from the soles of the feet to the top of the head, and then apply that measure to the outstretched arms, the breadth will be found to be the same as the height, as in the case of plane surfaces which are perfectly square.

[4] Therefore, since nature has designed the human body so that its members are duly proportioned to the frame as a whole, it appears that the ancients had good reason for their rule, that in perfect buildings the different members must be in exact symmetrical relations to the whole general scheme. Hence, while transmitting to us the proper arrangements for buildings of all kinds, they were particularly careful to do so in the case of temples of the gods, buildings in which merits and faults usually last forever.

English translation by Morris Hickey Morgan. Source (public domain): http://www.gutenberg.org/files/20239/20239-h/29239-h.htm#Page_102

In the original Latin:

De Architectura, Liber Tertius: Caput Primum

Illustration of Vitruvian man by Giovanni Giocondo (ca. 1433 – 1515) a.k.a. Fra Giocondo. He produced an illustrated edition of Vitruvius in Venice in 1511.

[1] Aedium compositio constat ex symmetria, cuius rationem diligentissime architecti tenere debent. Ea autem paritur a proportione, quae graece ἀναλογία dicitur. Proportio est ratae partis membrorum in omni opere totiusque commodulatio, ex qua ratio efficitur symmetriarum. Namque non potest aedis ulla sine symmetria atque proportione rationem habere compositionis, nisi uti ad hominis bene figurati membrorum habuerit exactam rationem.

[2] Corpus enim hominis ita natura composuit, uti os capitis a mento ad frontem summam et radices imas capilli esset decimae partis, (…) Reliqua quoque membra suas habent commensus proportiones, quibus etiam antiqui pictores et statuarii nobiles usi magnas et infinitas laudes sunt adsecuti.

[3] Similiter vero sacrarum aedium membra ad universam totius magnitudinis summam ex partibus singulis convenientissimum debent habere commensus responsum. Item corporis centrum medium naturaliter est umbilicus. Namque si homo conlocatus fuerit supinus manibus et pedibus pansis circinique conlocantum centrum in umbilico eius, circumagendo rotundationem utrarumque manuum et pedum digiti linea tangentur. Non minus quemadmodum schema rotundationis in corpore efficitur, item quadrata designatio in eo invenietur. Nam si a pedibus imis ad summum caput mensum erit eaque mensura relata fuerit ad manus pansas, invenietur eadem latitudo uti altitudo, quemadmodum areae quae ad normam sunt quadratae.

[4] Ergo si ita natura conposuit corpus hominis, uti proportionibus membra ad summam figurationem eius respondeant, cum causa constituisse videntur antiqui, ut etiam in operum perfectionibus singulorum membrorum ad universam figurae speciem habeant commensus exactionem. Igitur cum in omnibus operibus ordines traderent, maxime in aedibus deorum, operum et laudes et culpae aeternae solent permanere.

Latin text source: http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/vitruvius3.html

Los diez libros de archîtectura / de M. Vitruvio Polión; traducido en Español por Joseph Ortíz y Sanz (1787).

De la composicion y semetría de los Templos.

Woodcut illustration of Vitruvian man from the 1521 Italian edition translated by Cesare Cesariano (1475-1543) who made this and many other illustrations for that edition.

[1] La composicion de los Templos depende de la simetría, cuyas reglas deben tener presentes siempre los Architectos. Esta nace de la proporcion, que en Griego llaman “analogía.” La proporcion es la conmensuracion de la partes y miembros de un edificio con todo el edificio mismo, de la qual precede la razon de simetría. Ni puede ningun edificio estar bien compuesto sin la simetría y proporcion, como lo es un cuerpo humano bien formado.

[2] Compuso la naturaleza el cuerpo del hombre de suerte, que su rostro desde la barba hasta lo alto de la frente y raiz del pelo es la decima parte de su altura. (…) Todos los otros miembros tienen tambien su conmensuracion proporcionada; siguiendo la qual los célebras Pintores y Estatuarios antiquos se grangearon eternas debidas alabanzas. Del modo mismo, pues, los miembros de los Templos sagrados deben tener exactisima correspondencia de dimensiones de cada uno de ellos á todo el edificio.

[3] Asi mismo el centro natural del cuerpo Humano es el ombligo; pues tenidido el hombre supinamente, y abiertos brazos y piernas, si se pone un pie del compass en el ombligo, y se forma un círculo con el otro, tocará los extremos de pies y manos. Lo mismo que en un círculo sucederá un un quadrado; porque si se mide desde las plantas á la coronilla, y se pasa la medida transversalmente á los brazos tendidos, se hallará ser la altura igual á la anchura, resultando un quadrado perfecto.

[4] Luego se la naturaleza compuso el cuerpo del hombre de manera que sus miembros tengan proporcion y correspondencia con todo él, no sin cause los antiguos establecieron tembien en la construccion de los edificios una exacta conmensuracion de cada una de sus partes con el todo. Establecido este buen orden en todas las obras, le observaron principalmente en los Templos de los Dioses, donde suelen permanecer eternamente los aciertos y errors de los artífices.

Spanish text source: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor-din/los-diez-libros-de-archtectura–1/html/ff6e3736-82b1-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_89.htm

Image sources (all are in the public domain).

Leonardo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_Vinci-_Vitruvian_Man.JPG

Fra Giocondo: http://act.art.queensu.ca/pics-large/04ae308721bed18c761fbb374e817a71.jpg (with image cleanup work done by me in Photoshop, to erase the bits of text that were showing through from the other side of the page when the image was scanned without a black backing).

Cesare Cesariano: https://www.loc.gov/item/2006681079/ Library of Congress source page includes rights advisory “no known restrictions…”