Decameron Day 1 Novella 8 by Giovanni Boccaccio.

Translation (c) 2016 Christopher DiMatteo. All rights reserved.

Lauretta’s story, in which Guiglielmo Borsiere, with a witty reply, dismantles and transforms the stingy and miserly nature of messer Ermino de’ Grimaldi. Midway through the story there is a digression where Boccaccio, speaking through Lauretta, gives a scathing critique of the ill habits of courtiers.

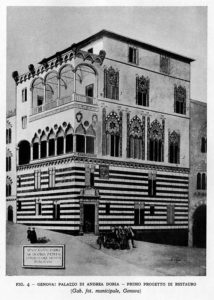

Design for restauration of the Palazzo di Andrea Doria in Genova (which is actually from about a hundred years after the time of this story).

Lauretta was seated right next to Filostrato. After hearing the praise for Bergamino’s cleverness in Filostrato’s story and knowing that it was now her turn, without waiting to be called, she happily started to tell her story:

The story we just heard, my dear friends, makes me want to tell you a story of how a worthy courtier, in a similar way and not without success, broke a wealthy man of the bad habit of avarice. It resembles the story we just heard, but you will not like it any less, since it does come to a happy end.

And so, in Genoa, some time ago, there was a gentleman named Ermino de’ Grimaldi. Everyone knew him to be the wealthiest man in property and money, whose riches far exceeded those of all the other richest citizens known all throughout Italy.

And just as he was the richest man that there was in all of Italy, he also surpassed every man in the country as, by far, stingier and more miserly than any other tight-fisted man even in the whole world. He not only never spent money on other people, but contrary to the customs of Genoa, where the people usually like to dress well, he never spent anything even on his own appearance, and the same for his eating and drinking habits. For these reasons, his surname Grimaldi had been deservedly replaced with the nickname “Mister Ermino Miser” which everyone used for him.

And so it happened that by not spending any money, he grew wealthier. Then, a worthy gentleman courtier, well mannered and well spoken, whose name was Guiglielmo Borsiere, came to Genoa.

He was nothing at all like the kind of courtier that you encounter today, who are shamefully corrupt and who practice every bad habit and who still want to be considered and called lords and gentlemen, while they are instead nothing but asses displaying all the ugliness and wickedness of the vilest of men that the courts produce.

It used to be at one time that their efforts were taken up with the work of making peace wherever there were wars or disagreements between men of good manners, or of arranging marriages, alliances and friendships, and with nice gestures and light-hearted words, of providing relief and entertainment to the court, and strict rebuke to the wicked, all for little in recompense. But today, they pass all their time spreading gossip, planting false stories about each other, telling tales of their wickedness and ill habits, and worst of all, right in front of each other, they accuse each other of faults, embarrassments and misfortunes real or imagined, and with false flattery, pass their time portraying gentlemen in vile and filthy stories.

And the one of them that is most admired by these miserable and ill-mannered men is the one who tells the most abominable lies. It is clearly to the great shame and blame of this world today, that the good old virtues have left us and abandoned us with these dregs of society and their miserable vices.

But returning to the story I was telling, since my righteous indignation took over more than I thought it would, as the story goes, Guiglielmo was admired and well received by the gentle people of Genoa, and after having lived for a few days in that city, and having heard many stories about Ermino’s stingy and tight-fisted habits, he wanted to see for himself. Mister Ermino had already heard that Guiglielmo Borsiere was a good man. Even he, as stingy as he was, had a flicker of kindness in him, and with friendly words and a smiling face he invited Guiglielmo to visit him. They talked about all kinds of things, and as they spoke, Ermino led Guiglielmo and some other Genoese friends of his, into his new house, which he had had built and beautifully decorated.

After having shown it to him, he said, “Well, Mister Guiglielmo, you who have seen and heard many things, could you tell me something that has never been put into a painting, which I can have painted in this room of my house?”

Guiglielmo, hearing his awkwardly phrased question, replied, “Sir, I don’t think that I could teach you about anything that has never before been seen in a painting, unless it were a picture of people sneezing or something like that; but, if you would like, I can surely tell you of one thing that I do not think you have ever seen.”

Mister Ermino said, “Well, if you please, tell me what it is,” to which Guiglielmo quickly replied, “Have the words ‘Kindness and Generosity’ painted on the wall.”

As soon as Mister Ermino heard these words, he was overcome with such a sense of embarrassment, that he felt like completely turning his mind and heart inside out, compared to what they had been until that moment, and said: “Mister Guiglielmo, I will have it painted in such a way that neither you nor anyone else will ever be able to say that I had not seen it and known its meaning.”

And from that day forward, such was the strength of virtue in Guiglielmo’s words, that Ermino became a most generous and gracious gentleman of his times, entertaining foreigners and Genoese alike, and remained the most honored among them all.

(Translator’s note: In the original Italian, what I have translated as “kindness and generosity” is “Cortesia.” I have used two words for one here, as the best way to render the blended shades of meaning between Italian and English, in the context of the story.)